Department of Endocrinology

On this page

- Download leaflet

- Introduction

- What is Congenital Hyperinsulinism (CHI)?

- How does insulin work?

- What goes wrong in CHI?

- Why is it important to maintain normal blood glucose?

- How common is CHI?

- What causes CHI?

- Genetics of CHI

- Transient CHI

- Types of persistent CHI

- What are the symptoms of CHI?

- How is CHI diagnosed?

- How is CHI treated?

- What happens after discharge from hospital?

- What if babies do not respond to diazoxide?

- What is prognosis for children with CHI?

- Where can I get more information?

Download leaflet

Congenital Hyperinsulinism (CHI) (291kB pdf)

Introduction

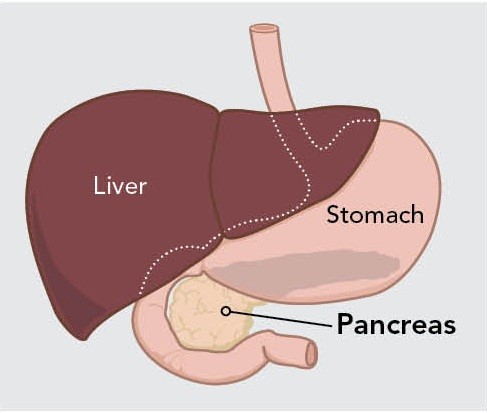

Congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI) is characterised by inappropriate secretion of high levels of insulin from the pancreas, which in turn leads to persistently low blood glucose levels. This leaflet explains about the causes, diagnosis and management of CHI in babies and children.

What is Congenital Hyperinsulinism (CHI)?

CHI is the most frequent cause of severe and persistent hypoglycemia (low blood glucose) in newborn babies and children. It is characterized by inappropriate and unregulated insulin secretion from the pancreas.

In CHI the beta-cells (cells in the pancreas) release insulin inappropriately all the time and insulin secretion is not guided by the blood glucose level (as occurs normally). The action of insulin leads to persistent and severe hypoglycaemia.

How does insulin work?

Insulin is a hormone, which controls the level of glucose (sugar) in the blood. Insulin is released by specialised beta-cells in the pancreas. As food is eaten, blood glucose rises and the pancreas releases insulin to keep the blood glucose in the normal range.

Insulin acts by driving glucose into the cells of the body. This action of insulin has two effects:

- Maintaining blood glucose levels

- Storing glucose as glycogen in the liver

During a fast, insulin secretion is turned off, allowing the stores of glucose in glycogen to be released into the bloodstream to keep blood glucose normal. In addition, with the switching off of insulin secretion, protein and fat stores become accessible and can be used instead of glucose as sources of fuel. In this way, whether one eats or is fasting blood glucose levels remain in the normal range and the body has access to energy at all times.

What goes wrong in CHI?

In CHI, the close regulation of blood glucose and insulin secretion is lost. The pancreas, which is responsible for insulin secretion, is blind to the blood glucose level and continues to release insulin despite low blood glucose level. As a result, the baby or child with CHI develops severe hypoglycemia and ends up needing large amounts of glucose to maintain normal blood glucose levels.

Why is it important to maintain normal blood glucose?

A blood glucose level less than 3.5mmol/l is considered as hypoglycaemia in babies and children with CHI. Babies with CHI are constantly reliant on a normal circulating blood glucose concentration for normal function of the nerves and brain, hence the importance of maintaining blood glucose level above 3.5mmol/litre.

CHI is particularly damaging because apart from hypoglycaemia, the insulin suppresses the release of alternative fuels called ketones. Hence the brain is deprived of both glucose and ketones.

Once the brain cells are deprived of these important fuels, they cannot make the energy they need to work and may result in seizures and coma. It is this cell damage which can manifest as a permanent seizure disorder, learning disabilities, cerebral palsy or blindness in the long run.

How common is CHI?

Hypoglycaemia due to CHI is relatively rare but potentially a serious condition occurring soon after birth. The estimated incidence of CHI is 1 in every 40,000 – 50,000 children although it is likely that the incidence is higher.

What causes CHI?

There are different forms of CHI. These can often be distinguished by the length of treatment required and the infant’s response to medical management. Some forms will resolve and are considered transient. Others arise from genetic defects and persist for life. These genetic forms of CHI do not go away, but in some cases, may become easier to treat as the child gets older.

Genetics of CHI

At present, there are nine known genetic causes of CHI, which can be inherited in an autosomal recessive (one mutation in the gene inherited from each parent, neither of whom is affected) or dominant manner (a mutation in a single copy of the gene). Abnormalities in the genes ABCC8 and KCNJ11 are the most common cause of severe CHI.

Transient CHI

Transient CHI means that the increased insulin production is only present for a short duration and is found in conditions such as:

- Intrauterine growth retardation (babies with low birth weight)

- Prematurity

- Infants of diabetic mother

- Infants with perinatal asphyxia (issues with low oxygen at birth)

Transient hyperinsulinism can occur in infants with no predisposing factors, the mechanisms causing this is currently unclear. Some of the transient forms of CHI will need treatment with medications for a few weeks to a few months; but generally, will be able to come off treatment at a later date. This will be assessed by a fasting study while off all medications to prove that the hyperinsulinism has completely resolved.

Types of persistent CHI

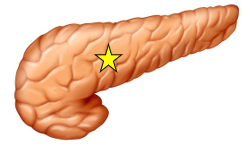

In children with persistent CHI, two main histological (appearance under the microscope) forms are noted: focal and diffuse.

Children with either form are identical in their presentation and behaviour. They tend to have significant hypoglycemia within the first few days of life and require large amounts of glucose to keep their blood glucose normal. They may have seizures due to hypoglycemia.

FOCAL CHI: A focal area of the pancreas is affected. Focal disease is always sporadic. Focal lesions are small, measuring 2-10mm.

DIFFUSE CHI: Diffuse CHI affects the whole of the pancreas. It can be familial or sporadic and can result from spelling mistake in the genes called mutations.

the whole of the pancreas

The management of diffuse and focal disease is different. Focal disease can be cured if accurately located and completely removed whereas diffuse disease, if medically unresponsive, will require a 98% pancreatectomy (surgery to remove the pancreas).

What are the symptoms of CHI?

Infants with CHI usually show symptoms within the first few days of life, although symptoms may appear later in infancy. Symptoms of hypoglycaemia can include floppiness, shakiness, poor feeding and sleepiness, all of which are due to the low blood glucose levels. Seizures (fits or convulsions) can also occur due to hypoglycaemia.

If CHI is not diagnosed and treated early, a child could develop brain damage, so ideally, children with suspected CHI should be transferred to a specialist centre. Alder Hey Children’s Hospital is one of the three specialist centres in the UK. These specialist centres have the expertise to carry out the detailed or repeated blood glucose monitoring needed to provide the appropriate treatment.

How is CHI diagnosed?

Once at the specialist centre, the initial task is to stabilise the child. This involves an intravenous drip of glucose and sometimes infusion of glucagon.

Access to large veins usually in the chest or tummy called a central venous access device may be required to administer high concentration of glucose, for obtaining crucial blood samples and for the rapid correction of hypoglycaemic episodes. A central venous access device is inserted into a large vein during a short operation under general anaesthetic.

Once a child is stable, the team will confirm or rule out a diagnosis of CHI. This is usually done through detailed blood and urine tests taken while a child’s blood glucose level is low. If his or her blood glucose level does not fall sufficiently low during the initial period, he or she may have a ‘diagnostic fast’.

As part of the fast, all feeds and fluids will be gradually reduced and then stopped for a period of time until he or she becomes hypoglycaemic (3.0mmol/l or less for a very short period of time only).

Once the fast has been completed, glucose is given into a vein to correct the blood glucose level back to normal.

In patients with persistent CHI, genetic tests and a special scan (DOPA – PET scan) will be required to differentiate focal from diffuse CHI.

How is CHI treated?

The aim is to keep the child’s blood glucose level stable (3.5 – 10mmol/litre). Initially, children are managed with high concentration of intravenous glucose containing fluids. Sometimes, glucagon infusion (a medicine used to release stored glucose in the body) might be needed. Subsequently children are established on feeds and started on the first line medications (diazoxide and chlorothiazide).

A heart scan (echo) will usually be done before starting diazoxide to rule out any underlying heart defect.

Diazoxide is an oral medication (given 3 times daily) that will aim to suppress the insulin secretion. The side effects include fluid retention and hence, it is always used with chlorothiazide (given 2 times daily), which is a diuretic (a medicine that induces water loss). In the long run, diazoxide can lead to excessive hair growth. This hair growth resolves several months after diazoxide therapy is stopped. Once children show a response to diazoxide, the intravenous fluids and glucagon infusion will be gradually weaned off.

Once the blood glucose is stable (and all intravenous infusions are discontinued), children will undergo a fasting test (to ensure that the glucose control is optimal) before discharge. The central line will be usually removed before discharge.

What happens after discharge from hospital?

Subsequent to discharge, it is important to monitor blood glucose regularly at home. Training will be provided to parents/carers for checking blood glucose by our nurse specialist. A detailed plan will be given to tackle any hypoglycaemic episode at home. Telephone contact and support will be available.

Children will be followed up in our outpatient clinic on a regular basis following discharge from Hospital.

Children who are on small doses of diazoxide will be admitted at a later stage to trial being off diazoxide.

What if babies do not respond to diazoxide?

In children, who do not respond to the first line medication, further investigations (genetic tests and or DOPA PET scan) will be needed to identify diffuse versus focal disease. In diffuse patients, octreotide, a medication which is given as 6 hourly injections can be tried. Diffuse patients who do not respond to medical therapy are likely to need surgery to remove the majority of the pancreas. Children with focal CHI will undergo surgical removal of the focal lesion.

What is prognosis for children with CHI?

Prognosis is greatly influenced by the form (severity) of CHI. The most important long term complication is neurological impairment. Brain function in CHI can be normal if hypoglycaemia has been diagnosed and treated quickly, but can be very variable depending on the amount of damage caused before diagnosis and treatment. With increased knowledge and research, the outcomes for these children are continually improving.

Where can I get more information?

The Congenital Hyperinsulinism Service at Alder Hey is one of three nationally commissioned sites for CHI in the UK. The other sites are Royal Manchester Children‘s Hospital and Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Consultant Paediatric Endocrinologists at Alder Hey

Dr Mo Didi Dr Jo Blair

Dr Poonam Dharmaraj Dr Urmi Das

Dr Senthil Senniappan Dr Ramakrishnan

Dr Didi & Dr Senniappan have a special interest in CHI

Dr Senthil Senniappan & Dr Mo Didi

Consultant Paediatric Endocrinologists

Nicole Falder

CHI Team Co- coordinator

Phone: 0151-252-5956

Email: [email protected]

Zoe Yung / Kelly Cassidy

Endocrine Nurse Specialist

Phone: 0151-282-4868

Email: [email protected] / [email protected]

Karen Erlandson- Parry

Advanced Paediatric Dietitian

Samantha Wright

Highly Specialist Speech and Language Therapist

Charlotte Aspinall

Clinical Psychologist

This leaflet only gives general information. You must always discuss the individual treatment of your child with the appropriate member of staff. Do not rely on this leaflet alone for information about your child’s treatment.

This information can be made available in other languages and formats if requested.

PIAG 32